2 Examples of Why You Must Challenge Your Confirmation Bias When Investing

Investopedia defines confirmation bias as:

“A psychological phenomenon that explains why people tend to seek out information that confirms their existing opinions and overlook or ignore information that refutes their beliefs. Confirmation bias occurs when people filter out potentially useful facts and opinions that don’t coincide with their preconceived notions.”

For example, if we start out with the preconceived notion that Apple is a great stock, we will selectively seek out confirmation (from news, analysis, reports, etc) that prove to us that Apple is a great stock. Even if we read reports of the new iPhone sales being a disaster or any piece of negative news, we will filter and ignore it to confirm our existing bias about Apple. This confirmation bias might cause us to hold on to Apple shares even when the signs are telling us that the company’s performance and share prices are falling. (Please note that this is just an example and is not my opinion of Apple.)

As you can see, confirmation bias can cause a lot of good investors to lose a lot of money. Even Warren Buffett has to fight his confirmation bias in order to be the investor he is today.

Warren Buffet and How He Avoids Confirmation Bias

It can be very difficult to counter confirmation bias because we have to come face-to-face with very uncomfortable facts and admit the possibility that we could be wrong. Warren Buffett faced this discomfort straight in the face when he invited his critic, Doug Kass, to Berkshire Hathaway’s 2013 annual general meeting. Doug Kass is a hedge fund trader and was widely credited for criticising Time Warner’s $112 billion acquisition of AOL in 2001. AOL was worth less than $3 billion when Time Warner spun it off in 2009.

Most of us would prefer to avoid potential embarrassment in front of a live audience which included 35,000 shareholders in Omaha and millions of investors around the globe. However, Buffett intentionally invited Doug Kass so he could play devil’s advocate and probe for any weakness in Berkshire Hathway’s investment and management plans. Buffett wanted to listen to his criticism so he could act accordingly before a bad decision haunts him. In other words, Buffett was not seeking confirmation for his investment decisions, he was actively seeking challenges when he invited Kass to his May 2013 shareholder meeting.

Kass did not disappoint viewers who were expecting tough questions from him. Kass publicly quizzed Buffett on a range of topics from whether he could continue to outperform the market given Berkshire’s size, Buffett’s succession planning given his age, and the anticipated winding down of the Federal Reserve’s QE program.

In response, Buffett replied that Berkshire remains disciplined in their purchases and would use their vast cash pool to pursue good deals for shareholders. Buffett kept his cards close on succession planning and expressed confidence in the Fed’s handling of monetary policy. Whether or not, Buffett agreed with any of Kass’s views, but it goes to show how far, publicly even, Buffett is willing to go in order to challenge any of his decisions and confirmation bias (if any).

Warren Buffett has a famous deputy named Charlie Munger and he has an equally rigorous defense against confirmation bias. Munger learnt to deal with confirmation bias from noted scientist Charles Darwin:

“Charles Darwin used to say that whenever he ran into something that contradicted a conclusion he cherished, he was obliged to write the new finding down within 30 minutes. Otherwise his mind would work to reject the discordant information, much as the body rejects transplants. Man’s natural inclination is to cling to his beliefs, particularly if they are reinforced by recent experience–a flaw in our makeup that bears on what happens during secular bull markets and extended periods of stagnation.”

As we know, Berkshire Hathaway, led by Buffett and Munger, is one of the most successful investment holding companies in the world. If you invested $1,000 in May 1980, your shares would be worth $614,065 (and counting) today. That is an annualized return of 120% a year — for 35 years.

Long Term Capital Management and How Confirmation Bias Killed Them

After we have seen how rigorously and publicly Buffett is willing to fight confirmation bias, let us examine how a noted hedge fund went bankrupt after they were blinded by confirmation bias.

Long Term Capital Management was founded in 1994 by John Meriwether. Meriwether was head of Salomon Brother’s bond arbitrage desk until 1991 and was responsible for 80-100% of Salomon’s global total earnings from the late 80s until the early 90s. He persuaded Nobel winners in Economics, Myron Scholes and Robert Merton, to join him on-board Long Term Capital Management as partners.

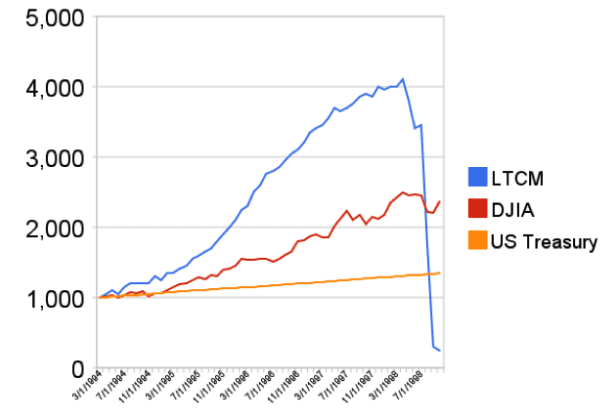

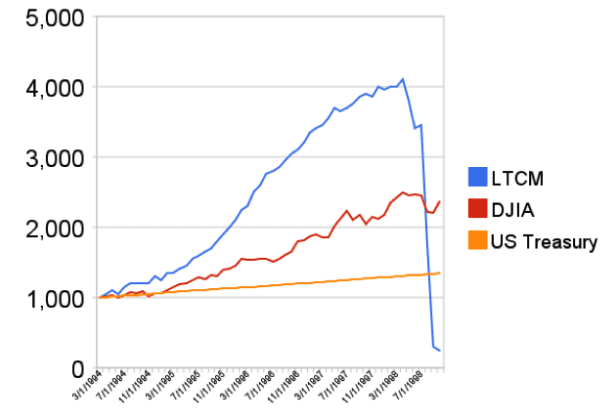

Long Term Capital Management achieved immediate success with a 21% return in 1995, followed by 43% in 1996 and 41% in 1997. These Nobel geniuses built a complicated mathematical model to predict prices and it seemed that they could do no wrong. Critics said though that the models would only work on a completely rational market and if markets panicked, Long Term Capital Management would stand to lose billions on its trades.

As it turned out, Russia defaulted on its government bonds on 17 August 1998. Global markets started to panic and the firm started losing massively when its highly leveraged trades started to go south. By the end of September, Long Term Capital Management’s equity value had fallen from $2.3 billion to just $400 million and was on the brink of collapse.

The value of $1,000 invested in LTCM. Kaput!

AIG, Goldman Sachs and Berkshire Hathaway offered to buy out the fund for $250 million and inject $3.75 billion into the firm. The offer was shockingly low to Long Term Capital Management’s partners and Buffett reportedly gave Meriwether less than an hour to accept the offer. The time lapsed before a deal could be worked out. In the end, the Fed had to bail the firm out to avoid a global collapse in the financial markets in 1998.

Total losses for Long Term Capital Management? $4.6 billion.

Despite the brilliance of its inventors, confirmation bias meant that Long Term Capital Management could not adjust their models to factor in the probability of a Russian default in August 1998. That single event practically wiped out the firm overnight.

Conclusion

Investment success is not about being the smartest person alive. The individuals behind Long Term Capital Management’s mathematical models were among the smartest people in the world but they could not see past their computations and confirmation bias.

Like Warren Buffett quipped:

“You don’t need to be a rocket scientist. Investing is not a game where the guy with the 160 IQ beats the guy with 130 IQ.”

Great post on the confirmation bias.

Unfortunately we are all human (I dare say) and as such we have inherited thinking errors from our friendly ancestors. Some of them are useful shortcuts but dozens are nasty biases that love to trick us into losing more money than we would like to pay for our ‘money lessons’.

Only the combination of opting for a simple, straightforward investing strategy and managing our complex emotions and biases is the path to success.

Hi Tacomob. Thanks for your kind feedback. You are right that we are prone to confirmation bias naturally. It is good to be aware of that and take steps to mitigate it. Steps would include outsourcing your investment if you are prone to that error or getting a critic to tear it down.

Another method which I didn’t mention on the article would be to write it down and review it again in a few days. The space of time would add clarity provided that your decision is not time sensitive of course. Good decision needs time and effort.

Thanks for your feedback and I hope to see you around.