Once left for dead, Crocs (NASDAQ: CROX) has staged one of the most stunning comebacks in retail. The maker of brightly coloured foam clogs went from a pop-culture sensation in the mid-2000s to the brink of collapse by 2009 – and then clawed its way back to become a growth darling in the 2020s.

At its peak in 2007, Crocs’ stock traded near US$70; a year later, a glut of unsold shoes and recession drove shares to barely US$1. Many wrote it off as a one-hit wonder. Today, Crocs is a multibillion-dollar brand that enjoys record sales and profits. How did this ugly shoe find its footing again? Let’s dive into Crocs’ roller-coaster journey, and the lessons investors can learn from its turnaround.

Phase 1: Hyper-growth and crash (2002–2008)

Hyper-growth: Crocs was founded in 2002 and burst onto the scene with an IPO in 2006, at the time that was the largest-ever U.S. footwear IPO. The quirky clogs, made from a proprietary ‘Croslite’ foam became a hot fad. By 2007, Crocs hit US$847 million in revenue, capitalising on a rapid global expansion. The company leveraged its patent-protected foam technology and low-cost, moulded manufacturing to achieve incredible scale. Crocs were everywhere, from mall kiosks to big-box stores, and virtually everyone who wanted a pair had bought one.

Overexpansion and the 2008 crash: Trouble followed the initial euphoria. Crocs overproduced inventory and expanded into too many products and stores, assuming demand would keep climbing. When the 2008 financial crisis hit, consumers cut back on non-essential purchases. Crocs suddenly found itself with mountains of unsold shoes. In 2008, the company lost US$185 million, and its stock plummeted from the high-US$60s to just about US$1 per share. The company faced shareholder lawsuits and even auditor warnings about its survival.

Phase 2: Initial turnaround (2009–2013)

Attempting to stave off bankruptcy, Crocs started closing factories, cutting a third of the workforce, and liquidating excess inventory. These moves stopped the bleeding; Crocs returned to profitability by 2010. However, after a few executive changes, the new CEO fell back into old habits, rapidly expanding retail stores and flooding the market with new styles (from flats to golf shoes) to transform Crocs into a lifestyle brand. By 2012, revenue had grown to US$1.1 billion, but growth stalled, and profits remained elusive. By 2013, the stock slid again, and management explored drastic options including a potential buyout.

Phase 3: Restructuring and refocus (2014–2020)

By 2014, it was clear that Crocs needed a fundamental overhaul. A US$200 million investment from Blackstone provided fresh capital and brought in new leadership focus. The CEO, who had overseen the overexpansion, announced his retirement. The mandate was to get back to basics and prioritise profitability over raw sales growth. Enter Andrew Rees, a seasoned footwear executive who joined Crocs in 2014 and became CEO in 2017. Rees would go on to orchestrate Crocs’ mega-turnaround, embracing a strategy of simplification, cost cuts, and a return to the core product.

Simplifying the product line: Rees aggressively trimmed the lineup eliminating underperforming lines like dress shoes and golf cleats. The company exited experiments that didn’t fit the brand – no more high heels or four-season fashion items. This allowed Crocs to focus its design and marketing on what made it unique: the classic clog (and a few related casual shoes).

Shrinking to grow: The turnaround plan also meant shedding excess overhead. Between 2014 and 2018, Crocs closed roughly 160 retail stores (nearly one-third of its global stores). It outsourced manufacturing entirely, even closing the company’s last two owned factories in 2018 to become a pure design-and-marketing firm. Around 180 jobs were reduced in a corporate headcount in a 2014 restructuring push. These moves yielded significant savings. In short, Crocs went from a bloated operation back to a lean, asset-light model.

Refocusing on the icon: Perhaps most importantly, Crocs’ management stopped treating its original clog as an embarrassing relic of the past. Instead, they embraced it as an iconic asset and doubled down on it. Rees believed Crocs had lost its identity by hiding the clunky clog in the back of stores and chasing every trend. Going forward, the company’s strategy would revolve around what Crocs does best. In Rees’s words, Crocs needed to drive ‘clog relevance’, reminding consumers why that flagship product is special. Rather than try to make the shoes prettier or more mainstream, Crocs leaned into their quirky appeal. Crocs essentially said, ‘Yes, we’re ugly, but we’re one-of-a-kind’ turning the brand’s former weakness into a point of pride.

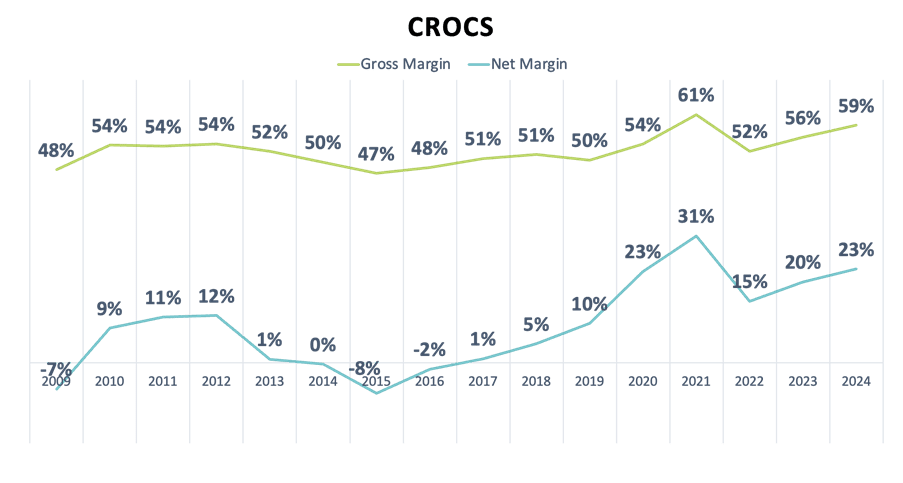

By 2019, the signs of progress were clear. Crocs had a smaller store footprint and a tighter product mix, yet sales were growing again. The multiyear restructuring paid off in improved profitability. Gross margins began trending up as the company shed low-margin product lines and achieved better economies of scale on its core clogs.

Phase 4: The comeback (2020–)

Crocs hit its stride in 2020 and beyond, aided by both strategic choices and serendipitous timing. The COVID-19 pandemic shifted consumer tastes sharply toward comfort and casual wear.

Doubling down on the icon: Rees and his team dramatically increased investment in the Classic Clog and closely related styles. Nearly two-thirds of Crocs’ design budget was redirected to clogs and sandals (away from fringe products), which raised the clog’s share of sales from under 20% in 2014 to over 50% by 2020. This focus created a virtuous cycle. With higher clog volumes, Crocs could leverage its moulding technology to lower unit costs and experiment with new colours and prints at scale. The result was a roughly 500 basis point jump in gross margin over this period, as the company benefited from economies of scale on its most profitable product.

Mass personalisation via Jibbitz: Another pillar of Crocs’ revival was turning a humble accessory into a high-margin engine. Jibbitz are small decorative charms that customers can pop into the holes of their Crocs. Crocs acquired the Jibbitz business in 2006, but it was an afterthought for years. Under Rees, Jibbitz was reimagined as a form of self-expression, especially for Gen-Z. Instead of just kiddie trinkets, Jibbitz became mini ‘identity statements’, tacos, rainbow flags, favourite characters, band logos – that let wearers customise their clogs.

The strategy worked brilliantly. Jibbitz turned a plain commodity shoe into a personalised canvas that begs to be collected and updated. By 2024, Crocs was generating US$271 million a year from Jibbitz charms, about 8% of total revenues. These add-ons carry superb margins (they’re cheap, and customers often buy several at a time), lifting overall profitability. Perhaps more importantly, Jibbitz create a repeat purchase flywheel: according to Crocs, roughly 75% of clog buyers also purchase charms, which boosts the average transaction value and encourages customers to come back for more.

Lesson for investors

Focus beats diversification. Crocs’ resurgence shows companies often succeed by amplifying their core strengths rather than chasing every trend. Previous management wasted years diversifying Crocs’ product range from sneakers to high heels, diluting the brand and hurting profitability. The turnaround began when Crocs refocused on what made it special: the Classic Clog and related comfort footwear. Beware of companies that stray too far from their core identity.

Capital-light and flexible. A key part of Crocs’ success was shedding heavy assets (stores and factories) and embracing a digital-first, direct-to-consumer model. This cut costs and made the business more agile and resilient. Capital-light businesses tend to be more flexible and better respond to changing consumer trends and economic shocks.

Small innovations can yield big results. Innovation doesn’t always mean expensive, high-tech R&D. Crocs demonstrated that smart, creative merchandising can deliver an outsized impact. Jibbitz charms, initially just a quirky novelty, grew into a US$271 million business by 2024. Sometimes, a simple idea can be as powerful as a patented technology. Well-conceived product extensions or add-ons can deepen customer loyalty, increase engagement, and drive repeat spending — all at minimal cost.

The power of new leadership. Crocs’ turnaround highlights just how transformative strong leadership can be. A visionary CEO like Andrew Rees came in with a clear mandate to fix the business. Equipped with a focused strategy and the courage to make tough decisions — from closing stores to slashing unprofitable product lines — he delivered remarkable results. His tenure proves that even a struggling company can be revived when leadership combines clear vision, disciplined execution, and a willingness to act decisively.

The fifth perspective

Crocs’ dramatic journey from near-collapse to a global success proves that even a struggling brand can reinvent itself with the right strategy and leadership. For investors, it’s a powerful reminder not to dismiss companies with strong core products or loyal customer niches. Under fresh management, those latent strengths can be transformed into a winning formula. Crocs achieved its turnaround by leaning into what made it unique and its unapologetic ‘ugly’ charm, while surrounding it with ingenious innovation, bold marketing, and efficient distribution. The lesson is clear: the stock everyone once mocked can become a stock worth owning. Crocs’ resurgence proves that yesterday’s punchline can grow into tomorrow’s powerhouse.