5 Reasons Why the Bank of Japan Introduced Negative Interest Rates

Negative interest rates used to be an exclusively European affair where only the central banks of Europe, Switzerland, Denmark and Sweden dared to venture. Japan became the first Asian country to introduce negative interest rates with its -0.1% decision on 29 January 2016. In simple terms, negative interest rates mean that instead of receiving interest on your money deposited, you pay an interest to keep your money with the bank.

The decision to impose negative interest rates was highly controversial. Bank of Japan Governor, Haruhiko Kuroda, was only able to push through with a tight 5-4 vote and negative interest rates commenced 16 February 2016.

Japan’s Negative Interest Rate Framework

Central banks are the “banks” for banks. This is the first concept you have to understand before I explain Japan’s negative interest rate framework.

For example, Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation (SMBC) becomes your bank when you choose to deposit money with them. Similarly, the Bank of Japan is SMBC’s bank when SMBC deposits money with the Bank of Japan. Japanese banks deposit money with the BOJ to store the aggregated savings of their depositors.

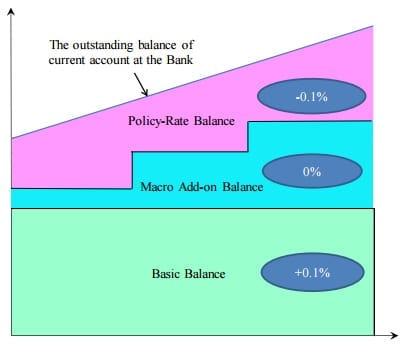

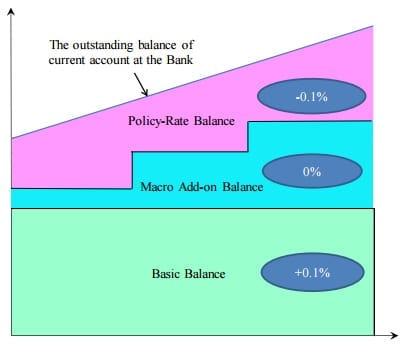

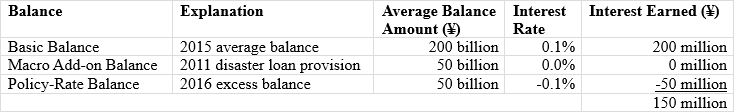

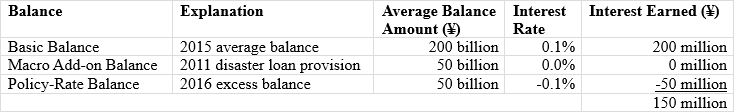

Moving on, the Bank of Japan introduced a 3-tier approach for its interest rates:

Source: Bank of Japan

Basic Balance

According to the BOJ, the basic balance is the average outstanding balance of each bank’s current account from January to December 2015. These are deposits not loaned out and the provisions for loans.

During this period, the BOJ purchased bonds, ETFs and other assets from commercial banks and the open market for its quantitative easing. In other words, the BOJ purchased these assets using Japanese Yen and the Yen is conveniently printed by the BOJ by pressing a button. The Yen is backed the full faith and credit of the Japanese Government and ultimately by its taxpayers. Hence, the Yen is the safest possible asset in the entire Japanese system.

Flushed with cash, this should make Japanese banks more willing to lend — in theory. Please note that I say ‘in theory’ but unfortunately this had not happened yet due to practical constraints.

Macro Add-on Balance

Do you still remember the Japanese earthquake and tsunami on 11 March 2011? The magnitude 9 earthquake hit North-eastern Japan and took down the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. This resulted in a level 7 nuclear crisis which resulted in over 15,000 deaths. Fukushima was the worst nuclear disaster since Chernobyl in 1986.

While this happened five years ago, emotions are still raw in Japan. Recently on 29 February 2016, Channel NewsAsia reported that a judicial review panel indicted former nuclear plant management for professional negligence which would open the first criminal trial for the accident.

The disaster caused Japan 25 trillion yen in damage and the BOJ pledged 15 trillion yen through the banking system to support the reconstruction effort. The amount financial institutions loaned for reconstruction efforts and the provisions for these loans are categorized as “Macro Add-on Balance” which will not earn any interest rates.

In other words, the BOJ is shielding the victims of the earthquake from the effects of negative interest rates. The provision might grow if the loans go bad when these victims can’t repay. If rates are negative, and even if provisions don’t grow, banks would respond by recalling the loans. They would repossess homes and other assets used as collateral. After all, banks are commercial entities not charities. The blame would then fall on the BOJ. This would cause a major political headache for the Abe administration.

If rates are positive here, banks might set aside more provision than necessary to offset the negative rates in the policy rate balance explained below. Hence, the Macro Add-on Balance is designed to offer exactly zero percent interest.

Policy-Rate Balance

However, any balance above the Basic Balance and Macro Add On Balance is known as the Policy-Rate Balance and is charged a negative interest rate of 0.1%.

So let me use the tables below to illustrate the entire framework using a fictional bank for example. Let’s assume that ABC Bank had a $200 billion yen in Basic Balance in 2015 and set aside $50 billion yen in Macro Add-on Balance for disaster loans. It also received $500 billion yen from Japanese depositors and the BOJ in 2016 and loaned out 450 billion yen. It would then have a Policy-Rate Balance of $50 billion yen.

Overall, ABC bank would earn 150 million yen in interest from the BOJ.

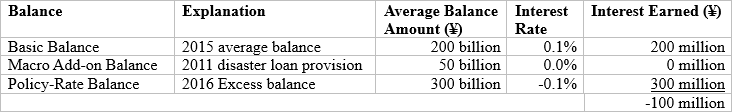

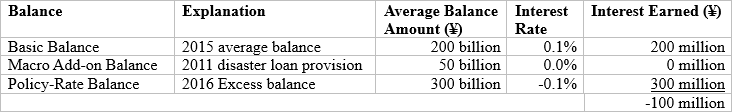

But if ABC Bank only loaned out 200 billion yen, it would then have a 300 billion yen in Policy-Rate Balance.

Then ABC bank would be charged 100 million yen in interest from the BOJ.

The BOJ will continue to conduct its monetary easing in 2016 at the annual rate of 80 trillion yen. So if Japanese banks continue to hoard the money earned from the BOJ, their policy rate balance will increase and they will have to pay more interest to the BOJ.

5 Reasons for Bank of Japan’s Negative Interest Rates

1. Force Banks to Lend Money to Stimulate Economic Growth

Now that you understand how negative interest rates are applied, you will understand the primary reason for them: To force Japanese banks to lend money which the BOJ has been supplying through its quantitative easing.

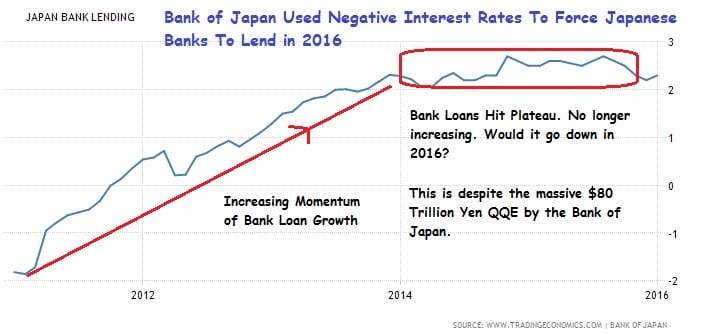

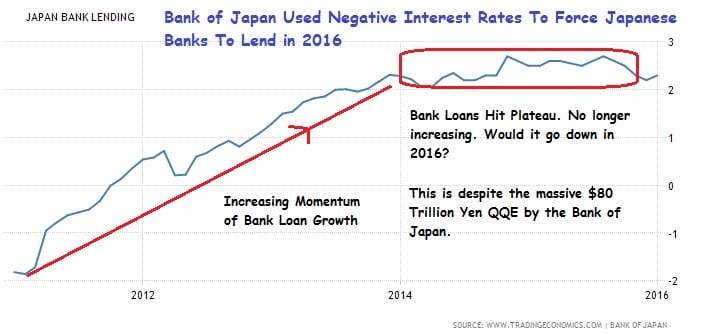

The BOJ started its quantitative easing in October 2010 to deal with deflation and a slowing economy. The purpose was to strengthen the bank’s balance sheet and to encourage them to lend. It worked from 2010 to 2013.

Source: Trading Economics

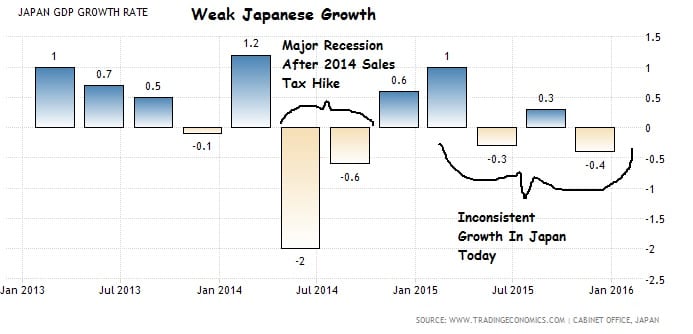

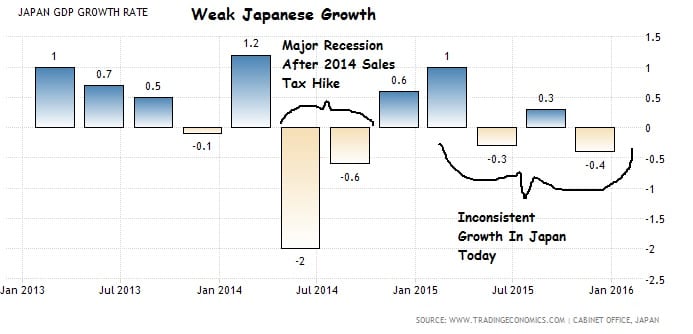

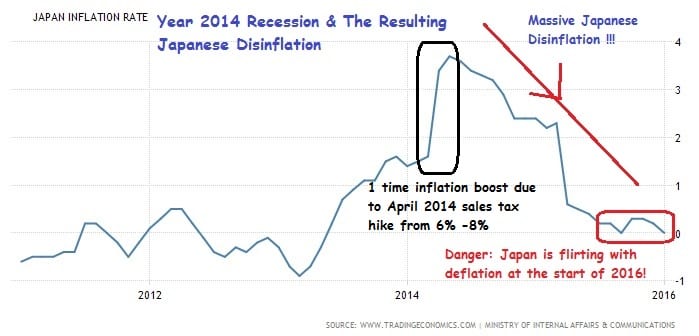

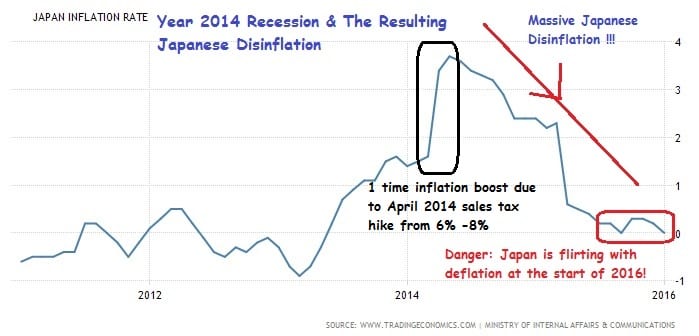

In 2014, Japan fell into a recession due to Abe’s sales tax hike.

Source: Trading Economics

As much as the Japanese banks wanted to lend more, they were constrained by the lack of demand for loans due to the recession. Japanese banks were so desperate to lend that they begged companies to borrow and backed their foreign investment deals. The situation was so bad that Citibank was forced to quit the Japanese market in 2014. For two years, the massive quantitative easing efforts by the BOJ did not work as they expected. Japanese banks were still not lending aggressively enough and the BOJ had to finally resort to negative interest rates.

2. Prevent Deflation

The BOJ had an official mandate to keep inflation at 2%. Mild inflation of 2% should encourage consumers to make purchases today instead of hoarding cash. This would lead to more investment and employment as companies increase capacity to meet demand. On the other hand, deflation encourages consumers to delay their purchases and previous economic weakness in Japan is largely blamed on long-term deflation.

Source: Trading Economics

The official inflation rate in Japan for January 2016 was exactly 0.0% and it does not take much for Japan to dip into deflation again. Disinflation has been going on since 2014 and it is apparent that the BOJ needs stronger medicine to defeat deflation.

“It should be noted that overcoming deflation as soon as possible and exiting from the low interest-rate environment lasting for two decades is essential for improving the business conditions for the financial industry.”- Bank of Japan

3. Fear in China

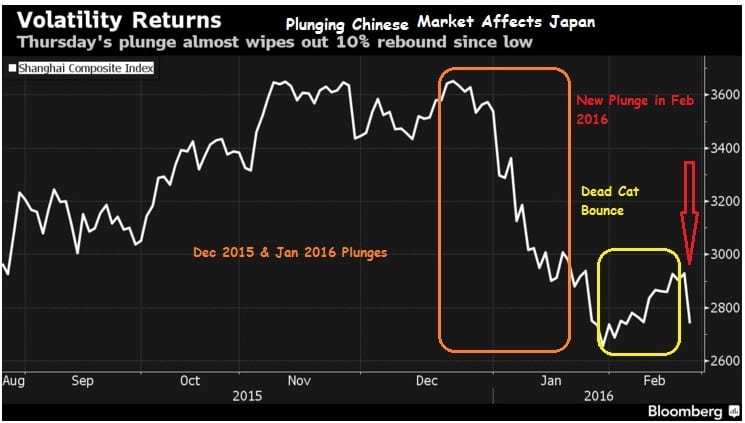

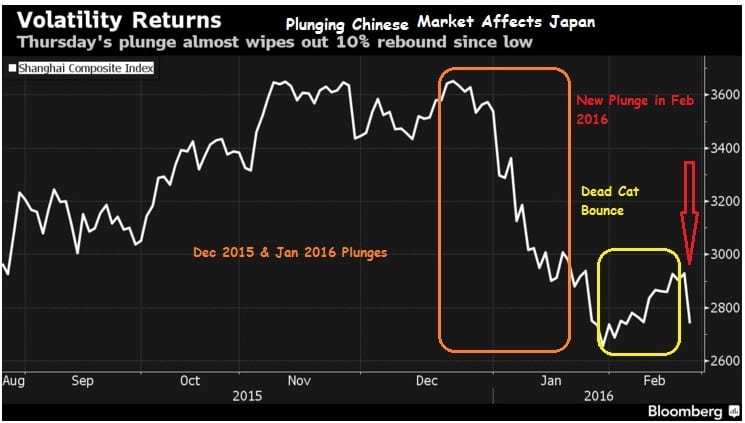

I previously wrote about how the Chinese equity market plunged three times in seven months from June 2015 to January 2016. After the article was published on 15 January 2016, China’s stock market plunged another 6.4% on 25 January 2016 as confidence evaporated and capital flowed out of China.

Source: Bloomberg

China worries pulled down the Japanese stock market by 11% in the second week of February and 21% year to date. The Chinese authorities made repeated pledges to stop the market rout after the June and August 2015 crashes. However, further crashes in December 2015 and January 2016 made clear that the Chinese authorities were helpless against the market plunge.

This encouraged the BOJ to introduce negative interest rates to defend the Japanese economy against further declines. China is the second largest economy in the world and Japan’s second largest export market after the United States; 18% of Japanese exports went to China, just behind the 20% that goes to the United States. If China were to have a hard landing, Japan would not be able to escape a recession.

4. Declining Oil Prices

Declining oil prices are supposed to be an economic boost for oil importing countries like the United States and Japan. However, economists view plunging oil prices as a hint for a future recession. Economists are split between whether the oil plunge is a result of oversupply or weak demand. While the case for oversupply is well-established and accepted, there is also a strong case for weakened demand as the Chinese economy continues to slow down. The slowdown is pulling down Japan’s economy and global economies around the world.

“The backdrop of the further decline in crude oil prices and uncertainty such as over future developments in emerging and commodity-exporting economies, particularly the Chinese economy. For these reasons, there is an increasing risk that an improvement in the business confidence of Japanese firms and conversion of the deflationary mindset might be delayed”- Bank of Japan

5. European Influence at Davos

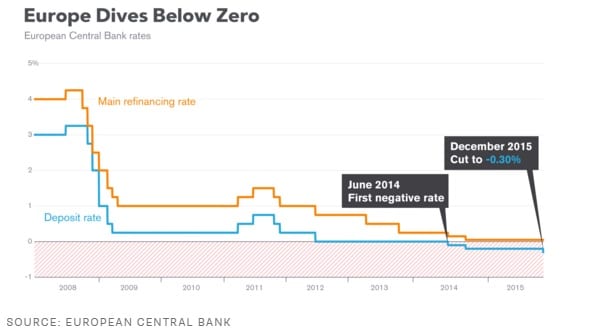

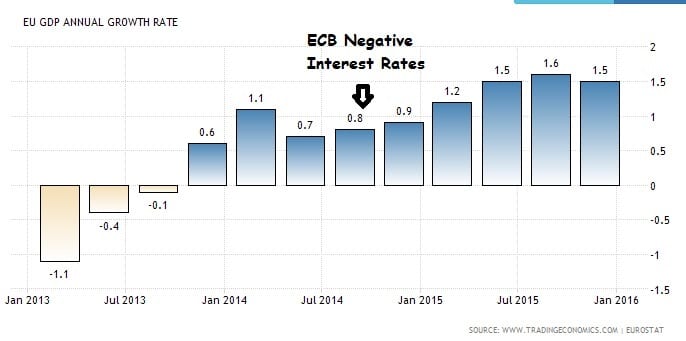

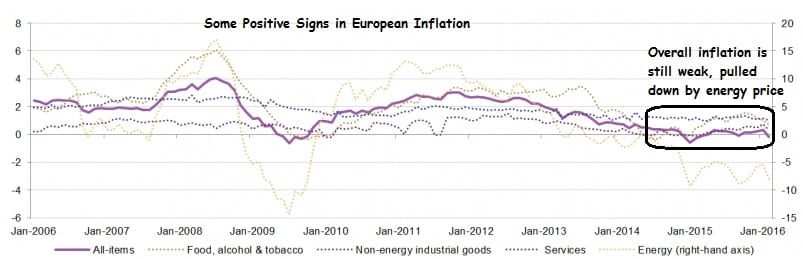

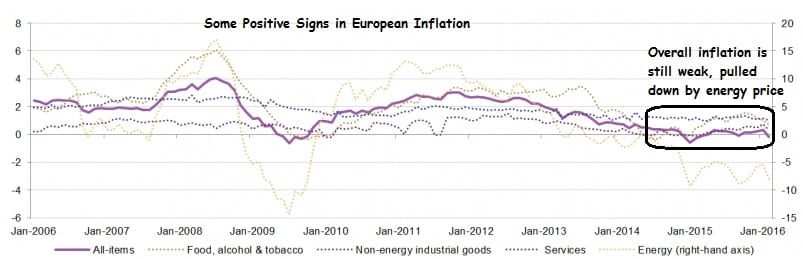

The European Central Bank (ECB) introduced negative interest rates in June 2014 to stimulate their economies. It was highly controversial at that time but ECB Chief Draghi kept to his convictions that it was good for Europe.

Source: Bloomberg

ECB was the first major central bank in the world to go negative in June 2014 and it followed up with a further cut on December 2015. This was the result in terms of Europe’s GDP growth. While the results were unspectacular, at least it showed consistent growth above 1% after two quarters.

Source: Trading Economics

So when BOJ chief Kuroda saw the European report card, he was persuaded to follow in the ECB’s footsteps. The ECB was successful in stimulating growth in Europe and it would have met its inflation target if not for the plunge in oil prices. Hence a case could be made that the ECB was successful and that steady growth would gradually increase inflation over time.

Source: Europa

Kuroda made his final decision to go negative during the Davos summit on 22 January 2016 after he rubbed shoulders with Draghi.

Reuters quoted a BOJ official as saying: “The ECB showed that combining QE and negative interest rates can work. It was just a question of overcoming some technical difficulties.”

Will It Work for Japan?

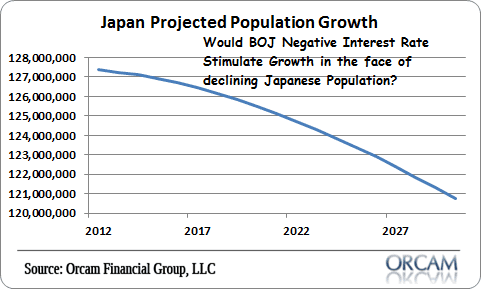

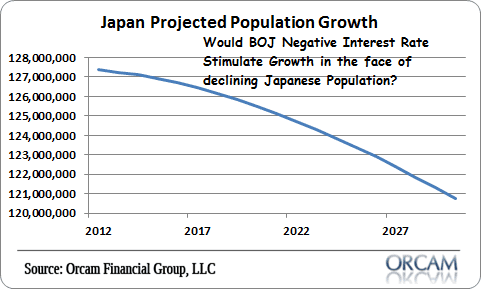

The effectiveness of negative interest rates is open for debate. While the BOJ can force Japanese banks to lend, the vital question remain as to who should the banks lend their money to? Banks have tried their utmost to lend and stimulate the economy but they were unable to find enough creditworthy borrowers to fill their loan books.

After being straddled with bad loans in the wake of the 1990s real estate bubble, Japanese banks have been highly conservative. They could conceivably choose to pay interest to the BOJ than to lose money on bad loans. At least, the blame is not on them.

Source: PragCap

While negative interest rates have worked for Europe, it is an open question for Japan. Europe does not have an aging population which is unwilling to spend and take higher investment risks. Europe has some relative success in its labour reform policies and it has the Investment Plan for Europe where European banks are able to loan money to infrastructure investment programmes with reasonable expectations of a positive return on their investment.

The Fifth’s Perspective

This might be Kuroda’s last successful attempt at negative interest rates due to the razor thin 5-4 majority. According to Reuters, BOJ board member, Sayuri Shirai who sided with Kuroda would be stepping down in March 2016. Kuroda’s ability to push for further negative interest rate would depend on nature of Shirai’s replacement.

For now, only time will tell if Kuroda was ultimately right in his decision to introduce negative interest rates for Japan. In the meantime, he will have to endure tough grilling in the Japanese parliament for his decision to levy what is effectively a 0.1% tax on the estimated 10-30 trillion yen sitting in the banks’ Policy-Rate Balance.

(Photo: Wikipedia)