The question of whether Elon Musk is being paid too little or too much has historically been a vicious debate among investors I know and follow.

Bulls argue Elon Musk is a genius, and that his vision and personal contributions to Tesla are what has allowed it to become what it is today. They believe that Tesla will make the electric vehicles, robo-taxis, and clean energy solutions of the future; and we should account for that in the valuation of Tesla.

Bears argue that Tesla is overvalued; facing fiercer competition from larger, more established automakers; and nowhere close to solving Level 5 autonomous driving yet. All this in the face of new reports that its cars are facing reliability and workmanship issues.

Regardless of whether you’re a bull or a bear on Tesla, let’s have a look at Elon Musk’s compensation package and decide if it’s fair. (Disclaimer: I am neither long nor short shares of Tesla.)

Some facts:

- Elon Musk famously receives no pay as Tesla CEO. His compensation is 100% tied to stock options.

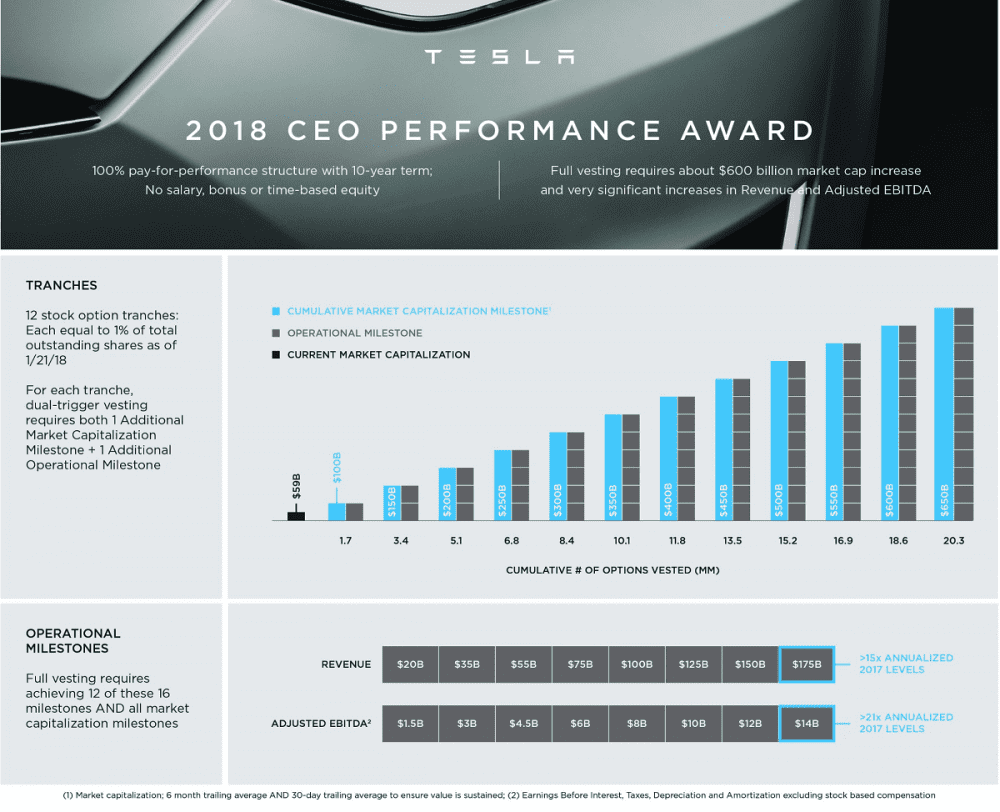

- Elon’s compensation package, set out in 2018, was a bold take: no salary, no cash bonus, no equity vesting. 100% at-risk compensation.

- There were 12 tranches of stock options, each one representing 1% of total Tesla shares. So if all 12 had been unlocked back then, Tesla shareholders would have been diluted by 12%. (Today, under new equity offerings to employees and via new stock offerings, each of those tranches are worth approximately 0.88% of total Tesla shares.)

- For Elon Musk to be awarded each of those tranches, Tesla has to achieve two goals simultaneously, (i) the market cap of Tesla itself must reach a certain level and stay there for at least six months, and (ii) either revenue or EBITDA must hit the necessary targets.

- Upon receiving the shares, Elon Musk must hold the shares for a period of five years. So, it’s not as if Elon could simply sell the shares immediately post receipt to earn a tidy profit. In addition, each share has an exercise price of US$70.01, which makes it a more than 90% discount from current prices.

Are these grants outrageous? On a surface level, they don’t seem to be. Musk’s fortune is tied to Tesla’s increasing share prices and a tandem increase in operational metrics. But on a deeper level, the operational milestones used raises some questions.

The use of adjusted EBITA, which Tesla defines as ‘net income (loss) attributable to common stockholders before interest expense, provision (benefit) for income taxes, depreciation and amortization, and stock-based compensation’ poses a problem for me. Why is this so?

Capital expenditure

For one, unlike software/technology companies where assets are not a large part of the business, Tesla needs steel for its cars, copper for its batteries, and Gigafactories to build all these things. Assets acquired for the purpose of making cars, batteries, and solar panels must be depreciated.

Property, plant, and equipment accounted for US$17.3 billion (29.9%) of Tesla’s US$57.8 billion worth of assets as of 30 September 2021. In comparison, Adobe, a software company, has a mere US$1.6 billion (6.1%) out of US$26.1 billion of total assets.

When a large part of your business value is made up of equipment you have to write down/replace/maintain, you incur costs that other businesses don’t. I can’t emphasize this enough: depreciation is a real cost.

Because Tesla cannot continue operations without reinvesting cash flows into equipment to keep factories and production lines running. If money is to be reinvested into Gigafactories, it is money shareholders will not see. If it is money shareholders will not see, then it should be accounted for.

“Does management think the tooth fairy pays for capital expenditures?” – Warren Buffett

In fact, if a fairer operational metric was to be considered, I would consider free cash flow per share to be the real value driver. Free cash flow is the money a business gets to take home after operational expenses and capital expenditure. On this end, Tesla turned free cash flow positive in 2019.

I have included a link to the Letter to Shareholders Jeff Bezos wrote in 2004. In it, Bezos used a simple example to highlight the difference between EBITDA and free cash flow, and why free cash flow is the ultimate measure of a company’s value. The five minutes spent would be well worth the read.

Regulatory credits

The second part of the problem is that Tesla’s earnings — and free cash flow — is distorted by its sale of regulatory credits. According to its Q3 2021 report, Tesla has booked US$1,151 million in sales of automotive regulatory credits this year. What are these credits they speak of?

Basically, automakers in the U.S., Europe, China, etc. are awarded regulatory credits for selling zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs), and automakers are required to reach a certain amount of regulatory credits each year. If they can’t meet the target, they can buy regulatory credits from other automakers that have excess credits (like Tesla). As you can imagine, Tesla, as a pure ZEV manufacturer, always has excess credits to sell. And these credits flow 100% to the bottom line.

Tesla’s nine months net income as of 30 September 2021 was US$3,198 million, of which we know Tesla received US$1,151 million in regulatory credits. So, 36% of the profits Tesla receives has nothing to do with its operational business. Tesla’s free cash flow was US$2,240 million, which means 51% of free cash flow was due to regulatory credits. The sale of credits artificially boosts Tesla’s EBITDA, which is one of the benchmarks for Musk’s compensation.

While Tesla should obviously take advantage of the regulations right now (it’s free money after all), other automakers will increasingly produce their own range of ZEVs reducing their need to purchase credits. This means Tesla cannot rely on the sale of credits over the long term to which they have already acknowledged:

‘What I’ve said before is that in the long-term regulatory credit sales will not be a material part of the business and we don’t plan the business around that. It’s possible that for a handful of additional quarters it remains strong. It’s also possible that it’s not.’ — CFO Zachary Kirkhorn

The fifth perspective

Elon Musk has an incredible visionary mind and has achieved what very few people could ever hope to achieve. I wouldn’t bet against the man succeeding and successfully replacing cars on the road with Teslas in the future. At the same time, I will have to consider some of the very real issues below if I need to value Tesla:

- ZEV credits are a short-term boost and distort Tesla’s earnings, EBITDA, and free cash flow.

- ZEV credits are due to government regulations; political winds can shift and change. Although government support for green technologies looks firm, if ZEV credit practise is changed in a way as to disallow sales, then Tesla’s earnings will be severely impaired.

- Capital expenditure and depreciation is a large part of any manufacturing business. This must be part of the equation if we were discussing operational and financial performance. Using EBITDA to benchmark Musk’s compensation masks this.

Elon Musk’s stock option grants effectively add up to around 10% of Tesla’s shares outstanding. At the same time, shareholders could argue that they stand to benefit greatly if Musk grows Tesla to a scale that would allow to him unlock all of his remaining tranches. Tesla has already surpassed the final market cap milestone of US$650 billion; what’s left are the revenue and EBITDA targets. Maybe if anyone can pull it off, it would be Elon after all.